Amidst disruptions caused by climate, social and technological change, sustainable districts offer a fresh urban planning approach for cities, said speakers at the Ecosperity Conversations. During the webinar, CLC's Research Director Dr Limin Hee showcased how districts can help cities achieve high economic performance, alongside high liveability and sustainability. Vice President of SP Group S. Harsha agreed that the district-scale can be used as a testbed to integrate urban eco-innovations such as district cooling and electric vehicle charging stations to offer an “energy as a service” approach for easy adoption, before scaling up.

Infographic summary of the Ecosperity Conversations webinar held on 24 June 2020. Source: Temasek

Webinar Speakers and Moderators (clockwise from top right): S. Harsha (Vice President, SP Group), Soh Hui Qing (Associate Director, Sustainability & Stewardship Group, Temasek), Dr Limin Hee (Director of Research, Centre for Liveable Cities), Frederick Teo (Director, Sustainability & Stewardship Group, Temasek) Source: Temasek

The proportion of the world’s population in cities is projected to increase from 55% today to 68% by 2050 according to the United Nations. There are numerous challenges for cities today, from public health risks, resource challenges, environmental stressors, economic and social disruptions.

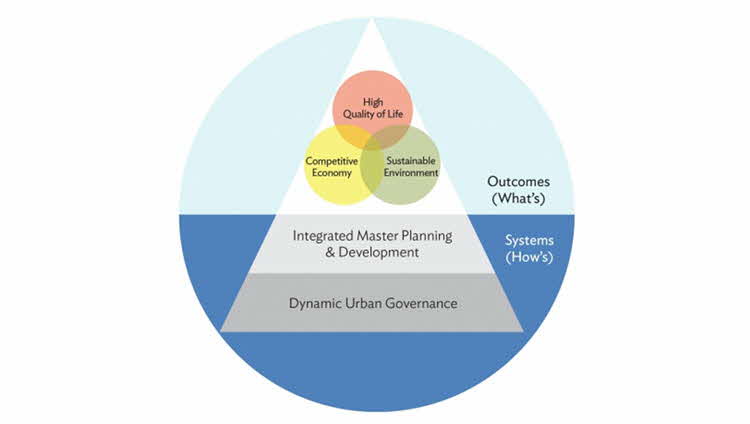

Singapore too faces such challenges associated with urban living. The city-state has done great work in the past where it overcame high unemployment, pollution and a lack of clean water and amenities. Its early leaders believed that sustainable development and economic growth must occur concurrently and took measures to ensure high liveability amidst its high density. The development of a sustainable, liveable and resilient city, with outcomes as illustrated in the Singapore Liveability Framework (Fig. 1), required a systems approach to urban planning, governance and innovation.

Figure 1: The Singapore Liveability Framework. Source: CLC

Climate change and resource scarcity are increasingly pressing issues for Singapore which necessitates greater investment of efforts to achieve sustainable outcomes while maintaining sustained economic growth. The Sustainable Singapore Blueprint outlines some of CLC’s aspirations for how we can do so by creating key targets in green and blue spaces, mobility, resource sustainability, air quality, drainage and community stewardship. Improvements in these areas build on both infrastructural and human capabilities to make Singapore a more sustainable city.

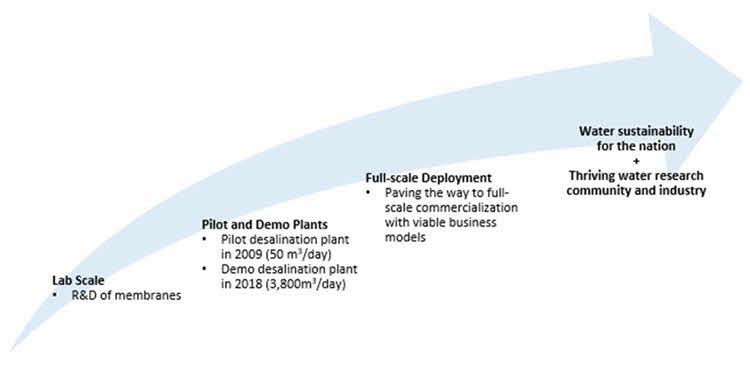

Singapore’s water industry development and urban systems innovations such as NEWater, the Deep Tunnel Sewage System and Active, Beautiful, Clean (ABC) Waters have shown that translation and deployment at scale is possible (Fig. 2). As a single agency, PUB can manage and scale up the translation and integration of urban systems innovations related to water, with clear leadership, good governance, research and development, and working closely with the industry.

Figure 2: Scaling up of water innovations such as desalination. Source: CLC

However, translating and integrating all urban system solutions into large scale deployment is more challenging. Not only does it involve various systems of energy, waste, mobility, as well as green and blue spaces, they cut across development boundaries. Currently, Singapore has introduced many innovations in the urban environment at the building scale. One example is the Building and Construction Authority’s (BCA) Green Mark Scheme for the development of environmentally-friendly buildings. Another is the Landscaping for Urban Spaces and High-Rises (LUSH) programme by the Urban Redevelopment Authority which encourages pervasive and accessible greenery in the high-rise urban environment. While these have helped the city-state become more sustainable, they are limited by scale. They do not cover all aspects of urban systems at work, and sometimes neglect the spaces in-between. On the other hand, introducing innovations at the city scale is complex because of the huge sunk costs in built infrastructure and greater legislative obstacles. The “sustainable district” thus offers an intermediate scale to testbed urban innovations as it is both flexible and has economies of scale.

Sustainability at the district scale

Sustainable districts are not new to Singapore. Since the Green Mark Scheme was introduced in 2005, a version for districts was created in 2009 and revised in 2013. The Green Mark for Districts recognises environmentally friendly and sustainable practices in master planning, design and implementation at districts of at least 20 hectares. Besides looking at energy, water and waste benchmarks, the criteria now also includes green transportation as well as stakeholder and community engagement. Some recipients include CleanTech Park (Platinum award) and NUS University Town (GoldPLUS award).

A local developer of sustainable districts is the Housing & Development Board (HDB), which oversees the construction of public housing towns in Singapore. It has piloted its framework for creating green and sustainable lifestyles, HDB Greenprint, in Yuhua in 2012 and Teck Ghee in 2015 (Fig. 3). These estates have been installed with new infrastructure such as pneumatic waste conveyance system, solar panels and sensor-controlled lighting so that HDB can assess their impact before implementing them at a wider scale.

Figure 3. Artist impression of HDB Greenprint in Teck Ghee estate. Source: Housing & Development Board

The Singapore government has laid the groundwork for private developers to participate in the development of sustainable districts. The best example is at Marina Bay where new buildings must achieve a Green Mark Platinum rating at minimum, which incentivises developers to pursue higher levels of sustainability. It also houses the world’s largest underground district cooling system, serving 23 buildings (roughly 1.25M square meter of gross floor area) including the Marina Bay Sands integrated resort (Fig. 4). Customers using district cooling not only enjoy energy savings of more than 40% but will enjoy space savings and upfront costs for on-site chillers. This frees up some 30,000 square meters of rooftop spaces for other uses like the infinity pool and restaurants on the top of Marina Bay Sands.

Figure 4. SP Group’s district cooling system at Marina Bay. Source: SP Group

The nearby Gardens by the Bay has also invested in sustainable solutions. In a pilot project with Singapore Power (SP), horticultural waste is fed to an on-site gasification plant which generates hot water for commercial usage. Waste volume is reduced by 95% through this process, minimising the need for transportation, and the remaining solid charred waste can be reused in the gardens. Other innovations include installing photovoltaic cells that provide clean energy for the destination’s light shows at night.

Singapore’s district development expertise is also featured abroad, in collaborative projects like the Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City (Fig. 5). A government-to-government collaboration between Singapore and the People’s Republic of China, the Eco-City spans 30km2 and, as of January 2020, houses a population of more than 100, 000 people alongside 8, 885 companies. In 2014, the Eco-City was designated as a National Green Development Demonstration Zone, including its “Eco-cell” system which encourages residents to walk more by distributing amenities in an accessible manner. Furthermore, the city emphasises on the conservation of the natural landscape as well as creating a strong industry and workforce. In 2019, the Eco-City also became a testbed for solutions such as the on-site recycling of plastics and organic waste. If proven successful, they will be replicated to other Chinese cities and Singapore as well.

Figure 5: Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City. Source: Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City Investment and Development Co., Ltd.

The above examples highlight how sustainable districts can help prototype liveable and sustainable urban environments without neglecting economic growth. More can still be done. An important area is creating a framework and tools to measure and compare the performance of sustainable districts so as to identify best practices and improve performance across the board.

Overall, sustainable districts offer a means of delivering liveable environments which integrate green and blue infrastructure and promote active mobility and wellness. They often employ the concept of circularity, leading to greater sustainability and cost-savings through optimising material resources, transport and energy. They require developers to work across boundaries and the same principle can be applied to both brownfield and greenfield areas— and is not limited to new developments. Sustainable districts are powerful prototypes that can lead to greater sustainability at the national scale and drive Singapore’s growth as a global hub for urban solutions.

SP’s sustainable energy solutions for Tengah: Innovations that can be scaled up?

SP’s work in Tengah, Singapore’s 24th HDB town, offers a glimpse of some innovations that have been introduced at the district scale. The first “smart and sustainable town” in Singapore will eventually house 120, 000 residents. Three of the town’s five residential precincts are part of the SP Group’s pilot project to adapt and deploy centralised cooling systems for residential use. Cooling systems are being installed on the rooftops of flats, where they are expected to accrue 25-30% of cost savings compared to traditional systems throughout their life cycle. In contrast to traditional air conditioning, these centralised systems are also expected to provide over 40% energy savings too.

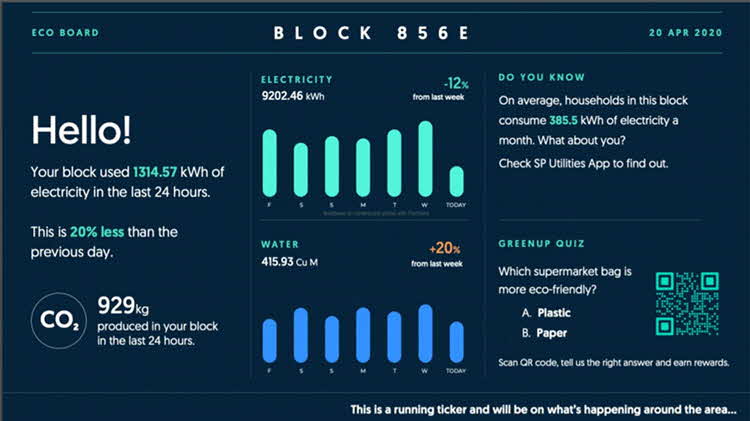

Such systems also present the SP Group opportunities to introduce and integrate other energy-related technologies into the built environment. Numerous initiatives are being planned, including the deployment of photovoltaic installations in the estate, gasification systems to allow for decentralised waste-to-energy recovery, charging systems for electric vehicles coupled with battery storage systems and sustainability-focused digital applications. Digital Eco Boards (Fig. 6) will also be put up around the estate, reflecting energy usage and updates about sustainability to residents on a regular basis. Two digital applications – MyTengah and OneTengah – will allow for residents and municipal operators respectively to monitor energy consumption and make changes in their own capacity to improve energy efficiency and enjoy cost savings.

Figure 6: A view of information presented on an Eco Board. Source: SP Group

With the centralised cooling system, the SP Group has also introduced a novel approach of “Energy-as-a-Service” to future residents of Tengah. Consumers will pay for cooling as a whole service, including recurring costs for chilled water depending on their usage, and periodic maintenance of the system. Such a model allows service providers to tap on economies of scale. It also benefits consumers in terms of cost savings, and residents who agree to the installation of the system ahead of time can have it installed in their homes by the time they move in.

As the system has higher upfront costs despite long-term savings, it will be key to work collaboratively with residents to secure their approval and financial support. Successful implementation in the long run would not just mean a proof-of-concept for technological innovations like the centralised cooling system but would also bode well for services providers looking to explore new business models.

Benefits of sustainable districts

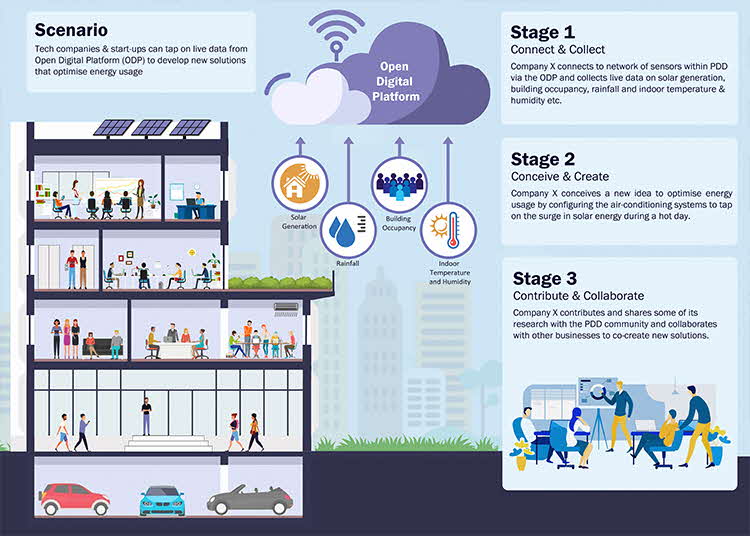

Singapore is currently developing other districts that show how greater sustainability can be achieved via district-level solutions. In Punggol New Town, the upcoming Punggol Digital District has the Open Digital Platform (Fig. 7) that allows public access to district-wide information collected by a network of sensors. Different users and businesses can tap on data and information provided by a common platform designed for interoperability. They can then contribute back to the community by sharing their findings and co-creating new solutions.

Figure 7. How the Open Digital Platform works. Source: JTC Corporation

Punggol is also Singapore’s first Eco-Town, featuring key developments such as My Waterway@Punggol. This living laboratory is jointly run by HDB and the National Parks Board to experiment with solutions to provide green cover, improve water quality and create spaces for recreation (Fig. 8 and 9). The town is also home to the Punggol Northshore district which will be planned according to a biophilic framework to promote and maintain biodiversity in an urban environment (Fig. 10).

Figure 8 and 9. A floating platform designed to create man-made wetlands in Punggol. Source: Housing & Development Board

Figure 10. Punggol Northshore artists’ impression, showing the implementation of a HDB Biophilic Town Framework featuring a dragonfly pond and incorporating native plant species into the landscape, as well as how green cover is integrated into recreational spaces. Source: Housing & Development Board

Through such sustainable districts, Singapore has created platforms for prototyping and eventually scaling up successful urban innovations. They are supported by flexible government policies and regulations that allow for piloting new technologies. For example, the deployment of floating platforms to encourage naturalisation and growth of mangrove plants in The Waterway@Punggol can benefit not just the districts but the entire city.

Currently, there has already been significant investment in R&D in the urban solutions sector by both the public and private sector. While some returns have been achieved, a gap remains in the translation of these efforts to large-scale deployment. Sustainable districts to scale up and prototype such solutions would help establish platforms for collaborations to realise the ambitious goals for better sustainable outcomes.

The authors would like to thank Temasek, SP Group and Dr Limin Hee, Director of Research of CLC for their inputs on the article.

This article was first published in Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC) and republished with permission granted by CLC.

A Singapore Government Agency Website

A Singapore Government Agency Website